As strange as it may sound, it was rear-end lameness that first attracted me to the Thoroughbred race horse. I was training and racing a few harness horses in the Fall of 1987 at the old Garden State Park in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. One Sunday, I was done with my morning chores and decided to walk over to a Mixed New Jersey Thoroughbred Sale that was taking place on the grounds. I run across a really nice grey stallion that had been a very impressive racehorse, earning over $100,000. It appeared he had just come off the track and that his connections were dumping him. He seemed to have clean legs, and he was a really nicely made individual. So, I was wondering, what gives? I went over him with a fine tooth comb. Tendons and ligaments seemed in great shape. I then got to his rear-end. I put my fingers over his whirlbone (a common area of soreness in the standardbred), and he about dropped to the ground! Wow, was he sore! His hocks were sore, too! I said to myself, I wonder if these run'n hoss boys know what rear-end lameness is? Being from the harness horse business, we have long known that the slightest soreness behind can really throw the balance of the trot or pace off! It is vital for our horses to be solid gaited so they will not break gait during a race. On the other hand, I suspected the Thoroughbred's gallop and running gait was much more forgiving to soreness. After all, a sore Thoroughbred was not going to change from the running gait, no matter how sore he is! He was going to simply not race well or break down. The nature of the Thoroughbred's speed gait, the run, opens him up to all types of abuse. Condition him under a trainer that is not a good horseman, that has a limited concept of soreness and uses drugs as a crutch, then no wonder such nice horses are dumped as no longer profitable or euthanized, if they break down. I was instantly intrigued with that concept which eventually pulled me into the run'n horse business.

To diagnose lameness, one of the first things to scrutinize are the hocks, even if the soreness is up front or high up on the topside! The hocks are often not only a problem unto themselves, but fosters upper rear-end and front-end soreness as a secondary form of lameness. To know when the hocks are off is the first line of defense in combating lameness in general. Below is the best hock test, I have ever seen and it was formulated by Dr. Edwin Churchill, a wizard! I was extremely lucky in getting my start in racing within his vicinity of veterinary practice, the Maryland / Delaware / Pennsylvania circuits. He was a huge influence on equine medicine in that region and developed one of the most useful hock tests that ever existed, but unfortunately, not very well known outside to the general public. Rear-end lameness is too often discounted as an unlikelihood in horses and this particularly goes for the racing Thoroughbred. I remember when I first left the Standardbreds for Thoroughbreds with a job at Hawthorn Park in Chicago. I was watching a track vet go over an animal and asked him if he saw much rear-end lameness? He told me, "no", and that seemed to be the prevalent view of practitioners and trainers when it came to the racing Thoroughbred 20 or more years ago. Maybe that has changed some in recent times, but I still suspect that hock and upper rear-end lameness is over-looked far too often. One probable reason for this, sore hocks are particularly hard to diagnose, if subtle lameness is involved. The Churchill Hock Test allows one to more accurately find such problems.

The below are selected summaries from a vet journal article outlining Dr. Churchill's methods and reasoning for this special type of hock test:

"The average race horse is a more emotional animal and may resist examination. Therefore, at the race track, horses are best examined in their own stalls, in familiar surroundings and preferably with their own grooms on the lead shank. To examine a horse accurately, it must be relaxed. Sometimes hand feeding during the examination facilitates relaxation. An examination that is performed with the horse twitched or having a chain under its lip is really not satisfactory. It pays to take time to gain the horse's confidence. Don't blame the horse for being wary!"

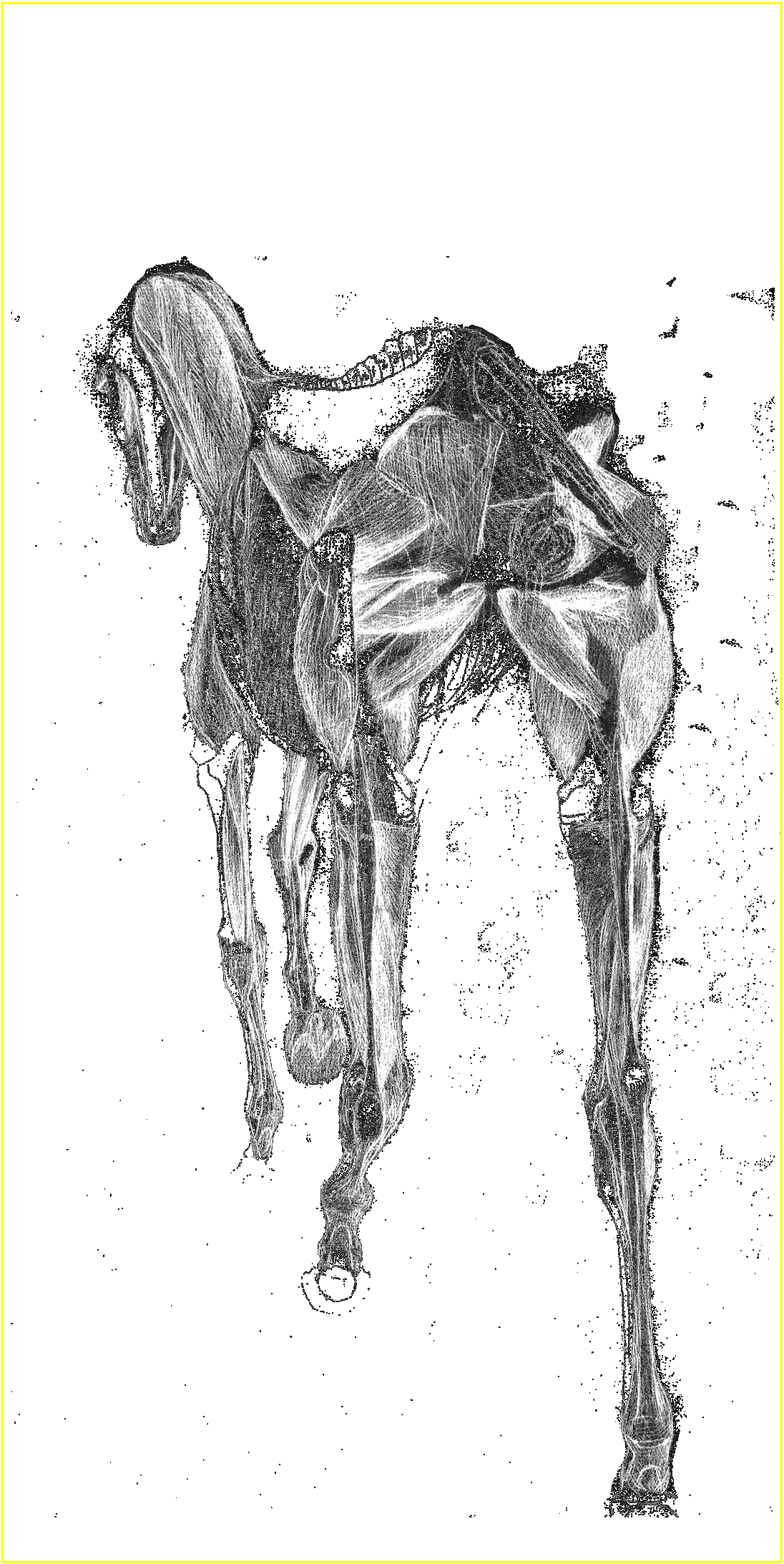

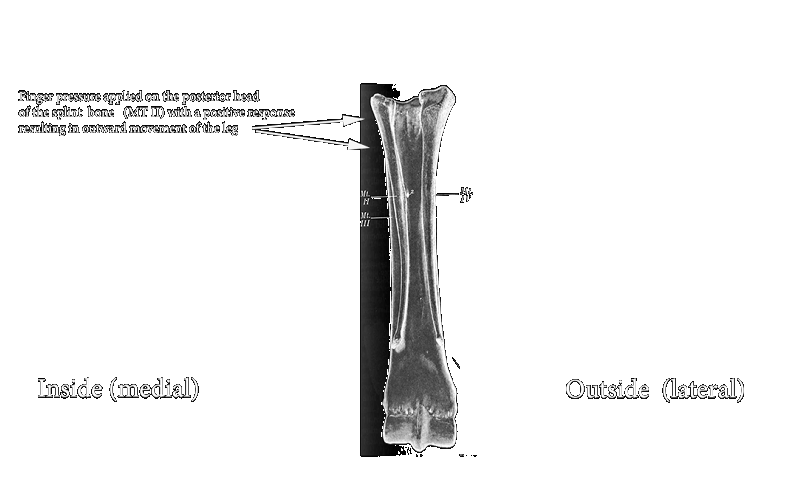

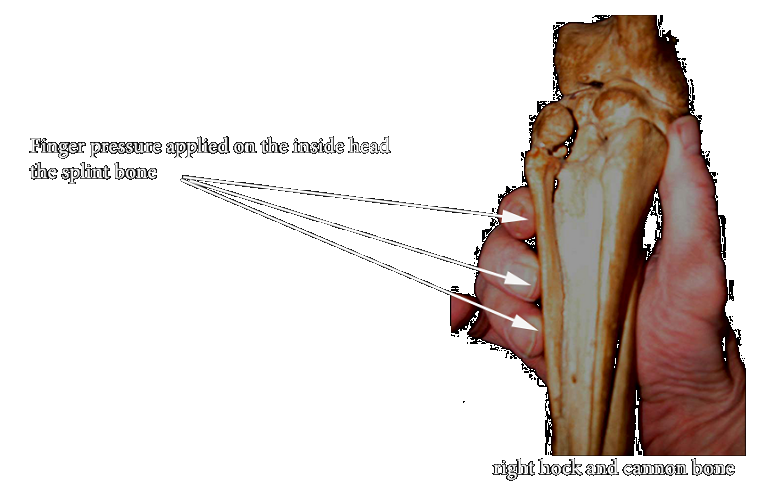

The left hind leg is picked up and supported by the right hand. The fingers of the left hand are curled around the medial face of the hock joint with the thumb across the anterior surface. With the left hand in this position but using only the index and middle fingers, pressure is applied to the posterior aspect of the head of the medial splint bone. This test is a specific for hock lameness, if the horse FLEXES and ABDUCTS the leg. Digital pressure should also be applied to the area of the cunean bursa in search of sensitivity. Now the opposite right leg is supported with the left hand and the hock test repeated with the fingers of the right hand on the posterior aspect of the head of the lateral splint bone.

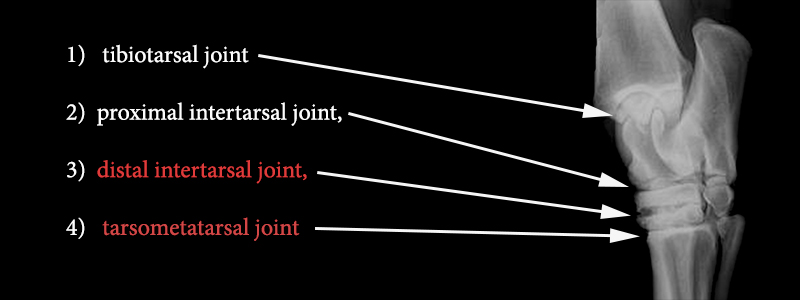

"If positive, it indicates a problem within the hock joint anywhere from the tibio-tarsal articulation down to the tarso-metatarsal articulation. It is not a spavin test such as the hock flexion test. The hock flexion test, at least for me, is almost useless in the diagnosis of lameness because a positive test can mean anything from trochanteric bursitis to sesamoiditis. It can be used as an aid in cases were a horse is not visibly lame. Then when the test is applied to each side of the horse it may help decide which hind leg is involved."

"The hock test described earlier in which pressure is applied to the head of the medial splint bone depends upon referred pain for its efficiency. I did not devise this procedure. It came about as a result of examining many thousands of horses for hind leg lameness. It gradually became apparent to me that pain over the head of the medial metatarsal bone was a constant finding in all types of hock lameness. It is my opinion that the alteration of the horse's gait is partially responsible for producing this pathognomomnic sign. By landing on the outside toe, excessive strain is placed on the medial structures of the tarso-metatarsal articulation including the second metatarsal bone. The same phenomenon is observed in the front leg. Excessive wear on the outside branch of the shoe of the front foot goes hand-in-hand with soreness of the medial splint bone of the same leg, including chronic splint formation. In early cases of hock lameness, pain over the medial metatarsal must be produced by extension from other areas of the hock. I strongly encourage you to try this test for hock lameness and not give up until you have perfected your technique. It is not something that you can learn to do in five minutes, but you can, once it has been learned, save yourself hours of time."

Summary for the Lay person:

I have found this test to be very valuable in detecting hock lameness, particularly if it is rather obscure. Note that Churchill says that this procedure has to be learned and you cannot go out and expect creditable results the first time out. You should practice this technique on every horse you come across and become accustomed to the various responses such a test may produce in individual animals.

In my own words without Churchill's anatomical jargon, let me run you through this test one more time:

Taking the left hind leg, you should pick it up and with the right hand, hold the flexed hoof in the palm of your right hand. I like to be in a squatting position so that I can rest my right forearm/elbow on my right knee/thigh while doing this examination. This cuts down on the examiners's muscle strain and allows you to concentrate on applying pressure to the inside head of the splint bone with the opposite hand. Ok, with the left leg being supported by your right hand, you take your left hand and place the thumb on the front part of the flexed hock with your index & middle fingers curling around over the inside lower portion of the hock--over the very top portions of the inside splint bone--you then apply intense finger pressure to this part of the splint bone. If the horse is positive for hock soreness, he will attempt to straighten and carry to the outside that hind leg. If he is negative for hock lameness, there will be no response. Repeat on the opposite hind leg, using opposite hands and fingers. I have long ago acquired hock bones from a dead horse to study on my own and know the structure of that joint as intimately as possible. I suggest you should do the same. It helps educate your fingers to what is felt under the skin. Practice on every horse you come across or is in your care!

This is a test that also works on the front-end as Churchill suggests. Lift the front leg and put pressure on the inside head of the splint bone. It may come in handy up front, too!