ANALYSIS AND SUMMARY

Even though this very interesting journalistic account of a typical training day on an American Thoroughbred race track took place some 95 years ago, much truth and perspective may be obtained from a current study with today's racing in mind. I will attempt to discuss my interpretation of its differences and similarities.

The 4:00 a.m. starting time for the race stable back then seems on the whole to be the same as today. However, the horses seemed to have been fed only twice in one day as opposed to the customary daily 3 rations-sequence followed today. The noon or mid-day feed has been skipped. Personally, when I trained a string, I never fed at noon either and my horses seemed not the least bit challenged nutritionally from that practice. Feed boxes of the past were also of the removable type. It is nice to know that close observation of the feed consumed and the cleanliness of the feed tub has long been a race track tradition and for good reason. Appetite is one of the most obvious indicators of well being in the horse.

The described communal dining of the help in the shed-row or rooming house is no longer customary among today's stable personnel as it was back then. Today, we have the track kitchen or cafeteria as the common spot for the entire track population to dine, not just one barn's crew. I might add that the common backstretch term of kitchen used on the track's backside for cafeteria comes directly from this tradition of unit kitchens serving each barn's crew. I would guess that few grooms receive a decent sit down breakfast anymore--no time with such early working hours observed. Most modern grooms will fall out of bed and go directly to work. Perhaps, they can get away for a quick coffee, but many never eat a full breakfast as it was observed so long ago. Instead of 5:00 a.m. being the breakfast hour, it is now the starting work hour that will allow the modern groom to prepare a horse to be on the track by 6:00 a.m. As always, modern life seems to have put a higher premium on time and labor.

Few trainers will make a stall-by-stall inspection of their horses upon arriving at the modern barn. Assistants or in smaller stables, the grooms, are usually the first vanguard to make such an inspection in this modern era. Should anything be amiss, they are the ones to notify the head trainer. Just as in yesteryear, feed consumption on an individual basis is one of the first signs that all is not well with a horse. As noted by the author, mares seem to eat less voraciously when compared to geldings or stallions. Some things never change, eh?

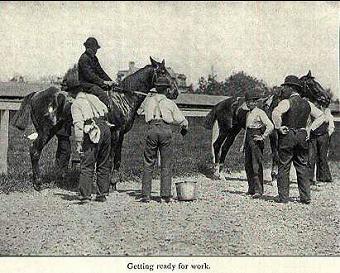

In this article, a set of six horses were sent out to work together in what is still to this day called a training set. You will only see such large numbers in a set at the larger stables of today. Most of smaller trainers can only work horses in sets of two, if we are lucky enough to be able to schedule two exercise riders at the same time. Mostly that is difficult, if not impossible. Certainly this is one of the prime benefits of training a large stable — the capability of working horses in large sets that more closely simulate actual racing conditions. One can teach a horse to come from behind, to cut the race on top, be brave on the outside, and a host of other things which would be impossible to teach working alone or in smaller sets. Interestingly, horses seem to be prone to just as much unruliness back then as now when being taken to the track. Horses were led by hand back then with no mention of a pony-horse ever being used.

Now comes the really interesting part of this article, the description of an actual work sequence. Wilfred Pond describes how these six horses were tacked up and led to the track. They enter at a nice sharp collected trot and travel the "circuit of the track" at that gait. Thus, this preliminary warm-up at the trot goes for about a 1-1.5 miles and, apparently, trotted the right-way of the track or counter-clockwise. As this set completes this initial warm-up at the trot, the trainer signals for them to break into a slow canter for about another mile with a final acceleration into a very brisk breeze, probably for the last eighth of a mile. After this very short breeze, the horses are brought back in front of the trainer where they are stripped of tack, sponged, rubbed down, and inspected. Now, the surprising part! Horses are tacked back up and a new set of riders are put on this very same set of horses. These new riders are more skilled horsemen. As the author writes, often the stable jocks were put up on the cracks (the best horses). The least experienced exercise riders were not allowed to go this second time around. Yes, another work for these horses without leaving the track! This all seems to have taken place within about 10 minutes. Next the trainer gives the riders more specific instructions as of distance to be traveled and time desired for that distance. Usually this second work takes the form of the riders jogging the wrong-way at a trot to a certain point on the main track, then turning in the counter-clockwise direction, and breaking into a faster gallop at the specified time instructed by the trainer. Finally at the very end of the work, the horses are often urged to their top speed or something close.

A typical trainer's instruction as given in this article: "Bob, take the colt to the ¾ pole, break him, and take him 4 furlongs in about :16, then breeze him home through the stretch." This means that the trainer wants the rider to jog his horse at the trot for about 6 furlongs from the finish line or to the ¾ pole of the track. Once at that pole, the boy would turn his horse, break, and cover the 6 furlong work by going the first eighth in 18 seconds, the second eighth (or furlong) in 16 seconds, the third eighth of a mile in :15, the fourth will go ideally in 14 seconds, the fifth furlong in another :14. The final eighth or furlong will be run according to the condition of the horse, hopefully close to top speed, if not top speed. In other words the first 5 furlongs went in 1:17 with the last eighth at top speed, whatever that may be. This initial rate of speed would be very similar to what is called a 2 minute lick in these modern times, just prior to going the last eighth at speed. If this account is accurate and I suspect it is close, then the old timers appreciated how speed can kill a horse. Speed was to be nurtured, never squandered. Horses were never forced. The old time trainers knew as we should know today that forcing a horse seldom comes to good and that moderate work speeds are the best way to develop fitness without injury.

Next the author talks how important it is for a rider or jock to have a "clock in his head". Unfortunately, I suspect this skill is becoming more and more a thing of the past. Modern emphasis is lost on the importance of clocked time to most young riders currently coming up. It was mentioned that the famous jockey, Todd Sloan was a marvel at this innate ability to measure time while on top of a horse. I would venture here to suggest that Todd Sloan's real claim to fame of the past was not in his adaptation of the monkey seat that has now become the norm among race riders and often penned on him as the originator, but to the contrary, his success racing abroad, was more due to his ability to gauge pace at which the Europeans were very poorly developed that led to his great fame as a race rider.

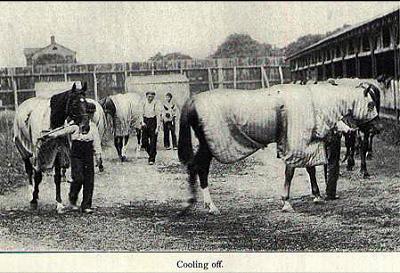

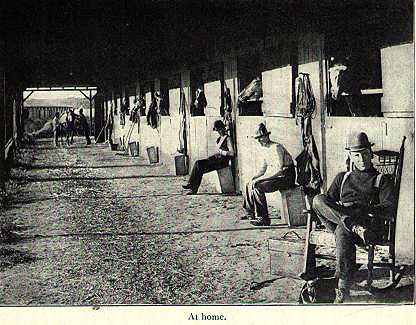

Now with the work over for our set of horses, they are taken back to the barn, striped, bathed with soap, and scrapped--all just as typical today as back then. The mention of the sand bath in this article is still adhered to, to some extent, in modern times. However, you will find this luxurious practice more a function of a training farm rather than those stabled at most metropolitan race courses. Horses seem to have been cooled out very similarly back then as today. Mechanical hot walkers are often the norm at most modern race tracks around the country, simply due to the lack of appropriate help. Once the horses are brushed and presumably done-up in bandages, if needed, they were allowed to rest the remainder of the day. I found it interesting that both Dutch-doors were intentionally closed during the latter part of day to insure a quiet time for each horse. The quiet atmosphere of the resting afternoon shed-row was closely guarded by the trainer. One will note that back then the grooms provided their own music via chants and ditties. Today, we have the often blaring radios hanging from the barn walls, broadcasting out rap or salsa. I doubt if this change is much for the better.

At 5:00 in the afternoon, the half-doors are opened letting the horses again view the outside world. Some are taken out to walk, some were not. This is the approximate time that evening chores are still scheduled in the modern race world as well. Most of the time, afternoon races will be long over by 5:00 pm. Horses are fed, watered, hayed, and stalls picked out at this time. Hooves were packed with peat-moss or clay. This seems to be a practice largely lost to most modern thoroughbred racing barns. It seems that only horses with obvious hoof problems are packed anymore. Back 100 years ago, all horses seemed to have had their hooves packed routinely. I have always done that with my own string, though I did not wait till 5:00 in the afternoon. My horses were packed just before they were turned loose in the stall for the day. Also, it is probably unnecessary to go to all the trouble of wrapping the packed hoof with cloth as described. I have found that Bentonite clay will in most cases stay within the sole of the hoof without anything other than the naturally stuck stall straw capping it. Packing the hoof with clay and using hoof oil is not to be underestimated in maintaining a healthy hoof and prolonging a racing career.

Lastly, the author mentions that it takes 3 months to bring a thoroughbred into flesh for racing. I find this estimate to be a bit optimistic, even under today's speedy standards and this is particularly true when developing first-time starters. One thing that Pond does write which will be controversial in today's climate: "When in condition some horses can run a couple of races a week, others only one in about three weeks." I think this is basically true. Certainly the fit race thoroughbred, if given a proper foundation can race weekly without corrupting his form. Certainly such close racing was a common practice during the first half of the last century and reflects solidly on the careful preparatory conditioning that those horses underwent prior to racing. Few modern race horses are given the conditioning of the past which allows this type of racing form to occur. Most are lucky to be able to stand a race every 2-4 weeks. Wilfred Pond also says with great insight that some horses race themselves into condition, some need only light exercise, and still others need hard work. Each horse is an individual and must be trained as such for best results—as true today as 100 years ago!